Business Models and Curation

While up in Edinburgh, I visited the National Digital Curation Centre. Amongst the many interesting things we talked about was the pesky difficulty of applying business models to curation. Chris Rusbridge at the DCC differentiates between curation and preservation as:

- Preservation: something you do for the future, and

- Curation: something you do for both now and the future.

This is a useful distinction, although I would perhaps modify curation to be both preservation and facilitation, to make clear what the curator is doing for the current users (faciling their doing something else). In any case, this definition of curation works for us.

It’s rather easy to provide a business model for facilitation, but not for preservation. If what you do is only preservation, then one has a difficult road to follow in establishing a business model. You have no users, and the future value of what you preserve is probably unknown. You only have costs associated with ingestion and ongoing storage (+migration etc). What are the metrics associated with successful preservation?

If you do both, then the risk you have is that facilitation dominates over preservation, because the business model for facilitation is rather easier to determine, and metrics for measuring success are much easier to determine.

It turns out that the DCC ran (with the Digital Preservation Coalition) a workshop on such issues, at the same time as a subcommittee of the NERC Data Management Advisory Group (DMAG) met to discuss output performance measures (or OPMs). Clearly OPMs have to relate to the objectives of the organisation, which to some extent come down to the business model. I attended neither meeting, but Chris was kind enough to send me some key presentations (they should be available on the web at some point, I’ll update this page when they are). Sam Pepler from the BADC attended the DMAG meeting, so I’ve got some feedback from both.

The material Chris sent introduced me to the Balanced Scorecard approach (see here for an introduction to the balanced score card, but the basic idea is to apply more than just short term finances to evaluation of success, particularly when developing intangible capital). The espida group are applying this to digitation curation.

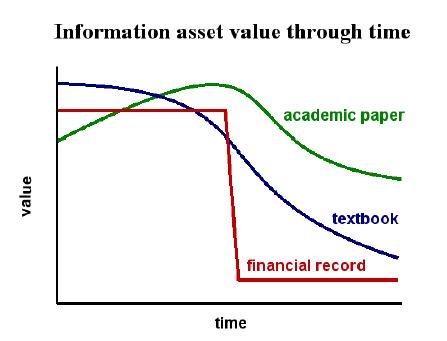

One of the things James Currall (from espida) appears to have talked about (at the curation cost model meeting) is the value-time behaviour of items, which he depicted in the following diagram (I will give a proper reference to where this comes from when I have one):

and he talked about a number of asset classes that one might look at preserving, which included research data. What struck me though was the implicit assumption in the above figure that all things decrease in value with time. Leaving aside how historians feel about that, I felt obliged to redraw his figure as follows:

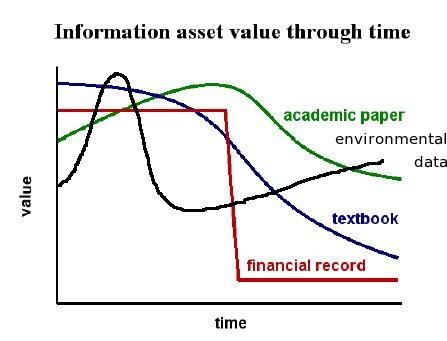

and he talked about a number of asset classes that one might look at preserving, which included research data. What struck me though was the implicit assumption in the above figure that all things decrease in value with time. Leaving aside how historians feel about that, I felt obliged to redraw his figure as follows:

The point I’m making is that for us, and for our science community, data usually has an immediate value, associated with (and preceding paper writing), and then, because it’s generally something about the real world, the value increases with time, as it becomes part of our timeseries of world observations (athough, until it’s used, which might be when the timeseries is “long enough” - whatever that means - we might have difficulty in justifying holding it).

This has implications on our cost model (and perhaps our balanced score card when/if we get to that). In this case, facilitation is generally about helping that first bump, and then preservation is about ensuring that the slope of the value time graph for environemntal data is positive!

The difficulty with our output performance measures is how to capture the latter. One of things that the DMAG subcommittee discussed was measuring the number of datasets published. Leaving aside the definition of publication, I would argue we need to measure the amount of ingestion work that is done (both of new datasets, which is generally hard, and of additional data for old datasets, which although it ought to be easier, is something we generally do badly in terms of updating metadata). Perhaps we can add to our list of criteria, the age of the datasets we hold - the older they are, and the more complete the timeseries, the more important they are - even if they have no current users. Worse still, if the timeseries is not being added to, and we have no (current) users, then how do we evaluate how well we are preserving it, and what resources should be devoted to doing so?

Update, August 2nd: James Currall tells me that when he actually gave his talk at the meeting the diagram had another curve on it: an upward increasing line representing the value of malt whisky with time … so he was already thinking about the class of things with values that increase with time (another example he suggested was artworks).

Me: I think wine would be a better example than malt whisky (which apparently always increases in value with time :-) … wine might or might not, but generally you don’t know til you open the bottle!

trackbacks (1)

Cost Models (from “Bryan’s Blog” on (on Tuesday 20 May, 2008))

Sam and I had a good chat about cost models today - he’s in the process of honing the model we use for charging NERC for programme data management support.

comments (2)

Chris Rusbridge (on Tuesday 02 August, 2005)

There are a couple of comments I’d like to make. First is that (to my mind at least) to qualify for curation, the “facilitation” stage you suggest must indeed stretch for “long enough” (in the OAIS sense). If you have a resource that you create, modify in various ways over a comparatively short time, and then put away in a facility such as BADC for later re-use, I think that’s much more preservation than curation. But if your use and re-use continues over an extended period of time, then it is likely some of the same issues that bedevil digital preservation will arise.

Not everyone takes this view; for example MacKenzie Smith from MIT sees the curator as the active person in the digital preservation process. But it works for me!

The second comment relates to “the justification for holding it”. I remember a comment from a major industry executive, to the effect that he knew half his advertising budget was wasted; he just didn’t know which half. Libraries know x% of the books they buy won’t be read… for a while; they just don’t know which ones (the same is no doubt true of environmental datasets). This thought helps me, from time to time, get out of a utilitarian trap! Librarians might say it’s what collection policies are for…

James Currall (on Wednesday 17 August, 2005)

With reference to the wine example, the value of wine is not simply what it tastes like (“value known when you open the bottle”), but a whole range of things, including what someone is prepared to pay for it.