The choice is python

Summary

This longer piece summarises my thinking as to what language folks like ourselves should use to develop new data processing (including manipulation and visualisation) tools. The context is clearly that we have data producers and data consumers - who are not the same communities - and both of whom ideally would use the same toolset. As scientists they need to be able to unpick the internals and be sure they trust them, but they’ll also be lazy; once trusted,tools need to be simultaneously easy and extensible. Ideally of course, one wants to develop toolsets that the community will start to own themselves, so that the ongoing maintenance and development doesn’t become an unwelcome burden (even as we might invest ourselves in ongoing support, we want that support to be manageable, and even better, we might want collaborators to take some of that on too)! The bottom line is that I think there are two players: Python and Matlab with and R and IDL as also rans, and that for me, Python is the clear winner - especially since with the right kind of library structure, users can mix and match between R, Python and IDL.

Introduction

For nearly a decade now, the BADC has been mainly a Python shop, even as much of, but not all, the NERC climate community has been exploiting IDL. The motivation for that has been my contention that

- Python is easy to learn (particularly on one’s own using a book supplemented by the web) - and that’s important when we are mostly hiring scientists who we want to code, not software engineers to do science,

- The Python syntax is conducive to writing “easier to maintain” code (although obviously it’s possible to write obscure code in Python, the syntax, at least, promotes easier-to-read code).

- Python can be deployed at all levels: from interaction with the system, building workflow, scientific processing and visualisation, and for web services (both backend services and front end GUIs via tools like Django and Pylons). In principle that means staff should be more flexible in what they can do (both in terms of their day jobs and in backing up others) without learning a plethora of languages.

Of course, one might make arguments like those about other languages, and folks do, but mostly I get arguments about two particular languages:

- IDL- which is obviously familiar to many (but far from all) of both our data suppliers and consumers, and

- Java - particularly given the Unidata toolsets, and because some of my software engineers complain about various (arcane) aspects of Python.

We’ll get to the IDL arguments below, but w.r.t. Java: it’s not really a contender, it’s simply not suitable as a general purpose language in our environment. It’s too verbose, it requires too much “expertise”, and it’s a nightmare to maintain. Some supporting arguments for that position are here (10 minute video) and here (interesting blog article).

In the remainder of this piece, I introduce some context: some results from a recent user survey at the BADC, a quick (and incomplete) survey of what is taught in a few UK university physics departments - with a few adhoc and non-attributable comments from someone involved with a much wider group of UK physics departments.

I’ll then report on a few experiences in the BADC, before summarising with my conclusions - which of course are both overtly subjective and come with considerable input bias.

Context: User Surveys

(This section is based on material collected and analysed by my colleague: Graham Parton.)

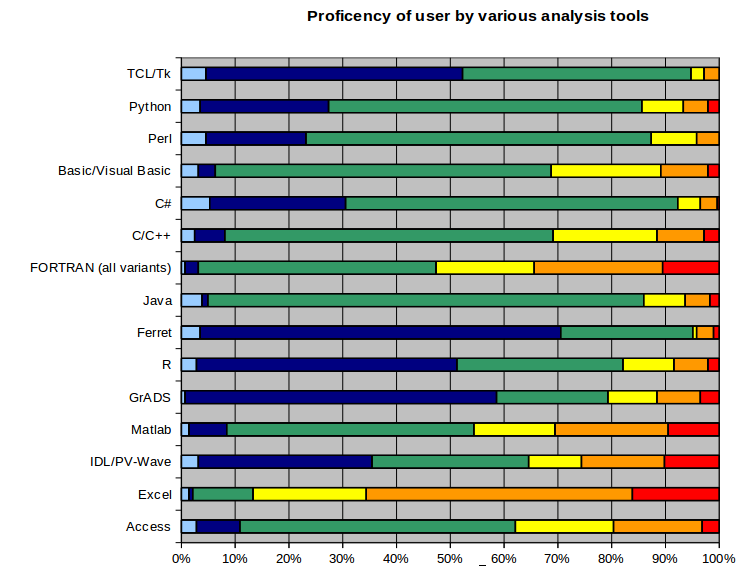

We surveyed our users and asked them about their proficiency with a variety of programming languages/packages: the basic results are depicted in this bar chart:

The results are from around 280 responses (Red means: geek level; orange: happy to use it; yellow: use it on and off; green: aware of, but not used lately: and blues : complete mystery or no response).

If we look at this, we see that

- The common scripting languages (Perl and Python) are not that commonly used by our community (but active Python usage is more prevalent than Perl and we can ignore TCL/Tk).

- Of the high level programming languages (Fortran, java, C and friends), Fortran is the team leader (as you might expect for our community).

- The big packages (Matlab, IDL, R) rank in that order (but note that R is more commonly used than python).

- GrADS has usage comparable to R and python, but Ferret isn’t much in use in our community.

- Excel and MS friends are common (but so is the influenza, and neither can do big data processing tasks).

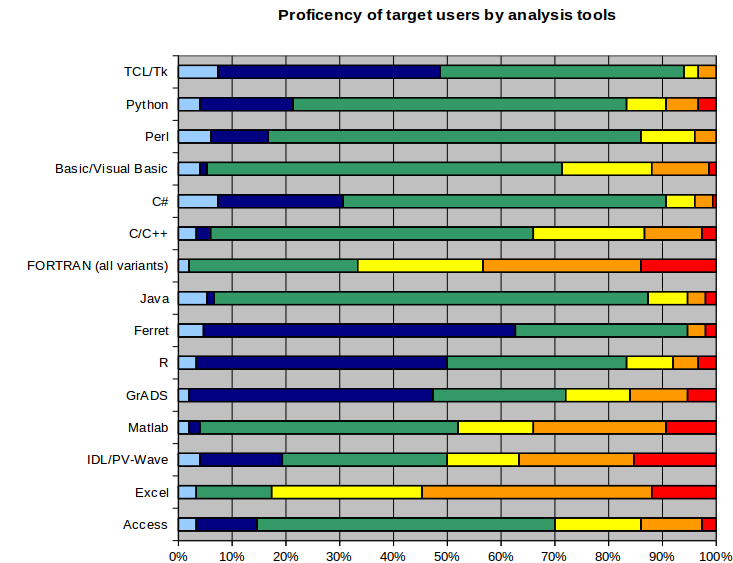

If we split all the responses into those from our “target” community (users who claimed to be atmospheric or climate related - roughly half of the total responses):

we find broadly similar results, except that IDL is marginally stronger than Matlab (at least as far as the usage goes - even if there is still more folk who are aware of Matlab). However, IDL still only hits half the audience!!!

Context: University Undergraduate teaching

Obviously most of the folks who use our data do so in postgraduate or other environments, and at least for NCAS, most of those will have IDL in the vicinity, if not on their desktop. However, what skills do they enter with?

As a proxy for entry level into our community, we (ok, Graham Parton again), did a quick survey as to what programming is taught in Russell group universities (why physics, why Russel group? Physics: graduates who are more likely to go under the hood … we’ll get back to that … and Russell: a small number of identified universities which we might a priori assume to have high quality courses).

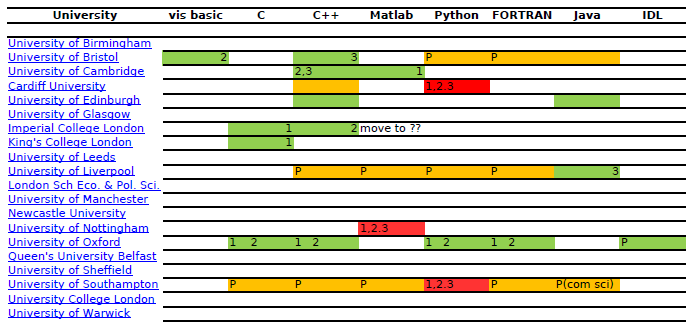

The results that we could get in an afternoon are here:

(Key: Red: integrated courses. Green: taught, Orange: accepted but not taught, P: project work, 1/2/3: year in which it is taught, if known). (We asked about some other languages too, but these are the main responses.)

What we find is that most of them offer programming courses to some level as an introduction to computational physics. There has been a move away from FORTRAN as the language of choice to other languages such as C++ and Python. Southampton, Cardiff and Nottingham have focused particularly on concentrating on one language that is integrated into wider course material (Matlab in Nottingham, and Python in Cardiff and Sheffield). These three universities have focused on one language to avoid confusion with others, focusing on aiming for fluency in programming that can be later translated to other languages as opposed to exposure to many languages. Oxford, on the other hand, is a notable exception where a wide number of languages are introduced in years 1 and 2. Imperial is reviewing programming provision and there is a strong lobby for Matlab within their department.

Most departments reported using a wide range of programming languages/packages (e.g FORTRAN, C++, IDL, Matlab) depending on what was the predominant processing package in the research group/field, e.g. IDL for astronomy, C++ for particle physics.

Overall, it appears that a ranking of programming language provision would be:

- C++

- MatLab

- Python

Off the cuff comments from a member of the Institute of Physics asked if they had any insight into the provision of programming languages in a wider group of physics departments suggest these results aren’t unique to the Russell group departments (but also that Python, having been off the radar, is increasing rapidly). That person had not heard of IDL (which is mostly used in research departments, and then mainly in astrophysics/solar-terrestrial/astronomy and atmospheric physics).

(Common feedback on why Matlab was chosen indicated that one of the drivers was the relatively pain-free path from programming to getting decent graphics at the other end.)

Discussion

At this point we need to focus down to some contenders. What should an organisation like ourselves, or even the Met Office for example, consider for their main “toolset” development language? Clearly on the table we have Matlab and Python (given the results above).

Given the importance of statistics to our field, and the fact that R is in relatively common usage and has an outlet for publishing code we should also keep it in the mix. However, if using R libraries is important, we can do that from Python … and it’s not a natural language for complex workflow development, so we’ll park R in the “useful addendum to python” corner … (that said, for a class of problems, we have used, and continue to use, R in production services at the BADC.)

What about IDL then? Well, clearly it’s useful, and clearly folks will use it for a long time to come. However, most ordinary IDL users are likely to be able to read Python very easily - even if they have never seen Python before: For a time we used to give candidates for jobs at the BADC a bit of Python code and ask them to explain what it did, and we only did that to folk who hadn’t seen python before. We had intended it as a discriminator of folks ability to interpret something they hadn’t seen before, but in most cases they just “got it right”. We obviously needed something a bit more complicated (in which case the more obscure Python syntax might have got in the way), but as it was, what we learned from that exercise was mostly that “Python is easy to read”!

What about writing IDL? Well, yes, it’s relatively straightforward, but it’s not a great language for maintaining code in, and it’s commercial (and not cheap!). The IDL community of use is rather limited in comparison to Python - and, you can call Python from IDL anyway. So if you really want IDL, but wanted “my new toolset”, (if we wrote it properly) you could call it from IDL anyway. (In this context, it’s worth noting that calling C and Fortran from Python is apparently much easier than doing so from IDL.)

There is clearly a lot of momentum:

- folk moving from IDL to Python, and some pretty coherent analyses of why one might use Python in comparison to IDL (e.g. here)

- There are also lots of web pages which provide information for folk migrating to Python from IDL (example).

We’ve seen that I believe python is easy to learn, and that at least two UK departments have built their courses around it. But what about the wider community?

- A number of computer science departments are now teaching Python as their first programming language as well (S. Easterbrook in private conversation).

- Probably more importantly for my thesis, is that the well regarded software carpentry course which provides an introduction to things working scientists most need to know uses Python.

- Clear climate code are using Python of course!

Which leaves us with Matlab. In truth, I don’t know that much about Matlab. My feeling is that the big advantage of Python over matlab is the integration with all the other bits and pieces one wants as soon as a workflow gets sufficiently interesting (GUIs, Databases, XML parsers, other people’s libraries etc), and the easy extensibility. You can use R from Python. You can even use the NCAR graphics library from Python (via PyNGL even if some are curmudgeonly about the interface).

The other thing that I believe to be a killer reason for using Python: proper support for unit testing: if we could inculcate testing into the scientific development workflow, I, for one, believe a lot of time would be saved in scientific coding. I might even rest happier about many of the results in the literature.

The Bottom Line

So, I’m still convinced that that the community should migrate away from IDL to Python, and the way to do that is to build a library that can be called from IDL, but is in native Python.

I appreciate that there may be some resistance to this, particularly from those scientists who like to look under the hood and understand and extend library functions. Some of those scientists are very familiar with IDL - but my gut feeling is that those are also the very same ones, that, if they spent an afternoon familiarising themselves with Python, would find they can go faster and further with Python. (Many of those folks are going to have been physicists, which was why I started by looking at what Physics courses have been up to.) My suspicion is that those that don’t look under the hood wont care, provided it’s easy to use, and well documented. Python helps with the latter too: with documentation utilities vastly superior to anything available in the IDL (and I suspect, Matlab) space.

So, after all that: the choice is (still) Python!

NB: I will update this entry over time if folk give me useful feedback.

comments (10)

Jon Blower (on Wednesday 13 October, 2010)

I might surprise you with agreeing with most of this, and in fact I’m planning to use Python (probably with CDAT unless someone can give me a better idea) to deliver my upcoming MSc module on data manipulation and visualization.

This is despite my being largely a Java fan, but (for climate sciences) only on the server side. I wouldn’t subject a typical climate scientist to Java programming, but not for the reasons you cite: “It’s too verbose, it requires too much “expertise”, and it’s a nightmare to maintain”. Java is absolutely, absolutely not a nightmare to maintain if written properly - try refactoring a medium-to-large project in Python, then do the same in Java and mostly one will find that the static typing of Java makes refactoring far, far easier, particularly with the help of a decent IDE. Verbosity is mainly a function of the APIs you’re using, not the language. Java does require more expertise than a scripting language, but I’ve learned that it’s not hard at all to teach Java to beginners (just don’t expect them to write a web server from scratch).

No, the main problems with Java on the client side in climate science are (i) the lack of high-level libraries to do the things we want (esp. on the statistics and graphics front) and (ii) the infuriating difficulty of interoperating with other languages (e.g. C, Fortran), meaning that it’s hard to reuse existing libraries.

On the server side, it’s a different story and that’s where the Unidata tools (and our own humble efforts) come in. The libraries are much more suited to server-side applications and you get to use all the existing mature Java server infrastructure. And in other communities, especially OpenGIS, Java stands alongside Python as a client-side language, mostly because there are lots of useful high-level APIs in this space.

Ideally of course, we’d like to use the same code on both the client and server side. This would be great but is harder than it seems. Client-side code is often not efficent enough for the server for various reasons, and the functionality an end-user needs is often different from what you need on the server side.

Finally, I don’t think it’s widely appreciated outside the Java dev community just how much goodness there is in Java libraries such as the Unidata stack and GIS toolkits like GeoTools and GeoToolkit. I’m afraid the Python tooling misses out on a lot of this good stuff at the moment. (Most of this is more relevant to server apps than client ones.)

But having said all that, I do love Python on the client side for scientific programming, although it’ll be interesting to keep an eye on R.

(Oh, and if anyone posts back to say “Java is slow”, I shall wittily retort, “1995 called, it wants its whinge back”.)

Nick Barnes (on Wednesday 13 October, 2010)

Thanks for the CCC link, Bryan. See also my article in Nature today http://www.nature.com/news/2010/101013/full/467753a.html which doesn’t mention Python for reasons of space.

Negative marks for Python might include space and time performance with large data or heavy processing. This is irrelevant for most scientists, and if it is a problem it can mainly be addressed with scipy etc, but it will still be a show-stopper for some users. So although Michael Tobis wants to write a GCM in Python, and I would certainly support that, I don’t think it’s likely to happen for a while yet. On the other hand, if we were going to do CMIP6 runs in it, we could spend some of the small change writing a killer high-performance compiler and numeric library.

Philip Kershaw (on Thursday 14 October, 2010)

I have to pick up on some of those points raised having written lots of IDL and Python. I like them both.

If we think of scientists who are novice programmers, support for IDL is very good. There is extensive help documentation all in one place and a great friendly user community. Now thinking of Python, the main site has great help pages but go beyond the core language to third party packages as users are likely to have to do a lot, and often they’re confronted with half finished or none existent documentation. One frustrated blogger writing about one package said they have to go to the C source code of the Python code, find the C library code the Python is wrapping and look up the documentation for that.

This touches on two other positives though, the Python C API is much, much easier than the IDL one, and that is contributor for its success. There are so many 3rd party contributions because it is open source a big plus over IDL.

I have to also raise something I mentioned on our internal e-mail thread on this topic. The poor support for encapsulation and the ability to dynamically assign new attributes to existing objects are big flaws. This is something IDL’s OO model does much better on. If people would use it.

Python has a permissive philosophy. Great if you know how to use it but a potential disaster for a novice scientist programmer or rather the person who has to use their code later. :) This is manifest as you scale up, as Jon notes, try refactoring a medium to large scale Python project and you realise. Not to say you can’t scale up Python, you can, but it needs to be written in a very disciplined way.

Yes, unit testing can help (PyLint is a must too) but we’re all human and a lot of software engineers aren’t that motivated to write them never mind scientists - even if they know what a unit test is. If however, you have a language where more of your checking is wired in the compilation or interpreter stages then the less you’ll be fighting with bugs later. I’d much rather have that than be picking through the pieces of some runtime error in a large system that’s just failed mid flow ;)

David Jones (on Thursday 14 October, 2010)

Obviously we (CCF) approve of your stance on Python. :)

It’s worth mentioning (perhaps you didn’t know) that Python has more than one implementation (another strength), one of which is Jython: Python implemented on top of the JVM. Jython allows Java libraries to be used in Python programs. I’ve never used it, but its not just a toy, real people use it for real work.

Looking at the bar charts it seems we should be doing everything in Fortran, Visual Basic, and Excel. Obviously that would be wrong (in so many ways), so what this really says to me is that I’m not sure the charts are all that useful for decision making.

One thing you don’t mention much but which I’m sure influenced your decisions, is community. To me this is the most striking difference between perl/Python/Tcl, sure there are technical differences that I’d be happy to debate for hours, but the real difference is that Tcl is dead and perl is moribund. Where can you hire a perl programmer now?

And just to buttress your support of Python: Over the years I’ve been using Python now, it has increasingly become my first choice to attack any problem. I’ve found it remarkably versatile and have used it for extremely diverse tasks: 2D image file creation, image analysis, audio processing, GIS mapping transformations, web applications, databases, scientific numerical processing, physical modelling, polynomial arithmetic, desktop GUI applications, system administration, investigations into floating point behaviour, and probably many more I’ve missed.

I think because I’m a programmer, I tend to think that any programming should be done in a general purpose programming language. Scientific programming is just programming. Financial programming is just programming. In my utopia, Matlab and Excel are banished.

Jon Blower (on Thursday 14 October, 2010)

David - good point about Jython. I had thought that project was moribund but checking back it seems like it’s active again. I actually used Jython for the first version of our ncWMS software, but abandoned it in favour of “pure Java” because of the difficulty of refactoring and maintaining a largish Python codebase (too many runtime errors!).

Sean Gillies (on Thursday 14 October, 2010)

“Try refactoring a medium to large Python project and …”

I’d give more weight to this statement if it was accompanied by links to code/repo/timelines of actual medium-to-large Python projects that you have tried and failed to refactor.

I’m a Python programmer who writes GIS packages. The language has tons of options that cover reading to analysis to visualization. Admittedly, support for OGC stuff is spotty. Some features of Python, like metaclasses, would seem to lend themselves very well to implementations of WxS and GML, but we don’t see much of this for whatever reason.

Daniel Rothenberg (on Thursday 14 October, 2010)

Another dimension to this discussion should address the issue of what sorts of technologies/tools we should be teaching to students and up-and-coming scientists. I’m another dedicated Pythonista - I’ve been using it for quite some time now, and it’s my go-to tool for tackling virtually any programming challenge), mainly because it’s so simple to bang out a cohesive, well-structured program in a short period of time.

I’ve advocated on behalf of Python to other students and faculty at my University, as well as at research centers where I’ve interned in the past. A huge, huge problem that I see among fellow students is that computer science and computer programming in general is viewed as some esoteric, high-level, non-practical exercise. For a generation of students who grew up performing statistical analyses by hand in Excel, the allure of Python’s great I/O and third-party scientific libraries is simply lost - mainly because their first exposure to ‘real’ programming is Fortran or some other dense, complicated language, which I’ve found to turn more than a handful of students away from programming entirely.

Especially in the atmospheric sciences, we should consider addressing the dearth of students’ programming skills alongside the issue of what tools are best suited for analysis and scientific tasks. A lofty goal would be to require a modicum of computer science training - something as simple as any intro to CS course which covers OO, simple data structures and simple algorithms. Perhaps a more attainable one would be to standardize what it is we’re teaching new students in terms of programming skills. A single semester of Python, with an emphasis on how it and libraries like NumPy/SciPy/Matplotlib can be used to crunch data and create visualizations, would be extremely beneficial. Adding in an optional Practicum which covered things like Fortran and more complicated applications/tools - sort of like how a CS undergrad would take a practicum in, say, databases or compilers - would be icing on the cake and useful for the subset of students who anticipate conducting research in the field.

In the meantime, though, I think the most practical way of winning converts to Python is to demonstrate its utility. For instance, this past summer I needed to find a way to quickly and easily visualize raw, binary output from a model running on a geodesic grid. A few days of work led to the creation of this tool - http://bitbucket.org/counters/geodesic-plotter/overview. And the embarrassing thing is that the bulk of that time was spent trying to get the binary I/O to work correctly - the documentation for MayaVi2 made the GUI/visualization part of the project a piece of cake. The tool’s hardly the best out there (VisIt, for instance, is MUCH nicer), but it got the job done - a job which was expected to take much more than a few days of work.

Jon Blower (on Thursday 14 October, 2010)

David - good point about Jython. I had thought that project was moribund but checking back it seems like it’s active again. I actually used Jython for the first version of our ncWMS software, but abandoned it in favour of “pure Java” because of the difficulty of refactoring and maintaining a largish Python codebase (too many runtime errors!).

Jon Blower (on Thursday 14 October, 2010)

Sean - yes, I guess I was thinking of Python library limitations in the OGC space, rather than GIS per se. For reading multidimensional rasters in scientific data formats (which is mainly what I do), I still prefer the Unidata Java tools. (GDAL and its bindings are wonderful if your rasters are 2D. I’m admittedly behind on CDAT raster compatibility.)

And regarding refactoring, admittedly my comment isn’t backed up with figures, but I was just making the point (to counteract Bryan’s assertion that Java is a “maintenance nightmare”) that static typing has lots of advantages, particularly in a multi-dev environment. Without static typing (and the discipline of coding to interfaces), one of your colleagues can make changes that affect you and you don’t notice till runtime when it breaks. In Java your IDE can tell you that sort of thing before you even hit “compile”. LOC count is not the only control on maintainability. Twitter moved from Ruby to Scala recently to get static typing among other things (http://www.artima.com/scalazine/articles/twitter_on_scala.html).

(I’m aware that this is a little off-topic from Bryan’s original post and I’m in danger of fuelling the usual fruitless Python-vs-Java debate, so I’ll shut up now.)

Ken Caldeira (on Sunday 17 October, 2010)

We do most of our post-processing of climate model output in python using CDAT, but I would never dream to write a model in it.

(If it is a toy model, I use Mathematica whiling cursing their usurious pricing policies. If it is a big model, I am probably modifying existing GCM code written in Fortran.)

http://www2-pcmdi.llnl.gov/cdat/