Interoperability is just over the horizon ... always

I’m not a GIS person, yet I’ve invested quite a lot of my own time, and quite a lot of public money, into building tools based around the Geographic Markup Language (GML). GML is essentially a toolkit designed to improve interoperability, but it’s getting a bit of bad press right now, both in blogs ( e.g.) and mailing lists (e.g this thread).

I probably wouldn’t care, but Sean Gillies who seems to have quite a few clues (and who provided me with the pointer to the blog link above), seems to agree. So I want to engage in this discussion, but before I do so, I want to digress.

I spend a lot of time arguing about how difficult it is to data citation and publication. One of the key points that one needs to keep on restating is that we have a shared understanding of what books, articles, chapters and pages are, and what those terms mean. We have no such understanding for data. Data is about the real world.

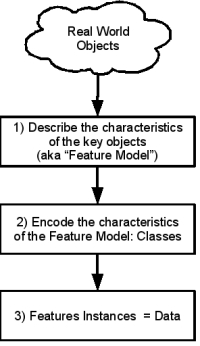

Ok: back to the main point. Interoperability, in the GIS sense, is actually the same problem. Actually, it’s the same point in every sense, not just the GIS sense, but we’ll stay focussed here :-). One of the best diagrams I have seen to make this point is in ISO19109 (Geographic information - Rules for Application Schema), and it’s encapsulated in one figure, which looks something like this:

The key point is that everyone, doing any coding, does something like that. We start off by modelling (on paper, in head, in UML … whatever) some of the things about the real world that we care about.

We then move from that abstract model to the world to building descriptions of the key features of the real world in some “descriptive language”. We give those descriptions names, likes “schema” or “standards” (or even “RFCs”) and we use a variety of technologies to do that.

Then we take data and we populate instances of those “schema”.

Really good architects/programmers find really simple ways of doing the process, so the entire effort is streamlined, and the resulting objects and instances are easily understood by the “Community of Interest”.

Now let time pass.

Two communities want to talk to each other, and exchange data. All that simplification is lost. They have to work their way back up the tree (probably to the real world level), and come back down until they share the same “descriptive language”, and then data objects described using the descriptive language can be shared.

On the way we can write a new descriptive language every time (for every pair of new communities), or we can try and design an abstract descriptive language that allows one to avoid that step every time someone wants to interoperate. Doing the latter introduces considerable complexity, and that makes the job of solving problems for ones own little community harder … every time. But, and here is the big BUT, unless you know you will never want to share your data, then you’ve just moved that complexity til later, you haven’t undone it. If you are in a business, that’s just fine, this years profit is all that matters, but if you have longer time horizons, then solving the tiny problem isn’t necessarily optimal.

Which brings me back to my data citation example. We can’t share anything, until we have a shared understanding of what it is (1), and a shared way of describing it (2). Right now, flaws and all, UML and GML are the best thing going for that. They’re absolutely not the best thing going for solving any specific problem, and not even close to the best thing for most of the use cases the GeoRSS community want to address, but, if you want to do interoperability, it’s not only today’s problem you need to think about: what’s over the horizon matters!

So, with that in mind, let’s go back to Charlie Savage’s argument. There’s a lot of good stuff there, but I think he draws the wrong conclusions.

Thus the real problem GML tries to solve is how can your computer system and my computer system exchange data about the world in a meaningful way? In my opinion that's an unsolvable problem, because the way your database models the world is different than mine.

So I agree except for the unsolvable bit … which we’ll come back to.

He ends up with

In my view, the fundamental premise of GML is wrong. The ability to create custom data models is an anti-feature that makes integration between different computer systems impossible because it assumes that those systems can actually understand the data. Computer systems have no such intelligence - they only understand what someone has programmed them to understand.

Which is so nearly right, except for the impossible and anti bits.

I think the heart of the problem is in the expectation of what GML gives you. What it absolutely doesn’t give you automatically is code to manipulate someone else’s data objects. What it does give you is a descriptive language you can both use to describe them, and you absolutely have to spend real programming time exploiting the fact you have a common language (so now it’s solvable and possible!) No, my WFS client may not understand your Feature Types … yet … but I could make it do so, and I can do that without inventing or learning a new paradigm. That’s interoperability, but it’s a “strong-typing/loose-coupling” sort of interoperability.

Of course it’s not the only sort of interoperability that matters. Web 2.0 and REST and GeoRSS and all that stuff is good, it’s really good, but it’s not the whole story. I wish folk wouldn’t keep on arguing that just because some technology doesn’t solve their use case it’s flawed!

Of course I can give you chapter and verse on why GML sucks, but that’s another story, it sucks less than some other options :-)

trackbacks (2)

Not Solving Problems (from “cfis” on (on Sunday 06 May, 2007))

Bryan Lawrence has an interesting response to my post about integration and GML. In his view, GML is not meant for data exchange but instead provides a common language that various communities can use to develop interoperable solutions. He fully understan

Whither service descriptions (from “Bryan’s Blog” on (on Tuesday 22 January, 2008))… there is a long tail of activities for which the abilities of web services to open up interoperabilty is being hindered by the difficulty in both service and data description …

comments (6)

John Caron (on Friday 04 May, 2007)

So, accepting all your premises, the question is:

“Is GML a good descriptive language for this domain, that will allow seperate parties to understand each other and create interoperable programs?”

It may be the best there currently is, but since we are taking the long view here, its fair to ask if it is really going to meet the test of time. Because if it isnt, lets understand why, and move on.

It could be that the process of creating OGC specs itself is flawed, perhaps because implementations come after the fact, perhaps because industry consortia are simply the wrong “governance” structure to produce clean technical specs with just the right level of abstraction.

It also seems to me that XML is hindering rather than helping the language clarity, and in particular XML Schema is close to a disaster. Part of it is that people seem to be doing object modeling in XML, rather than using XML as (one possible) representation.

I realize its easy to criticize and hard to do these jobs well. Im looking forward to your “why GML sucks” blog entry. Ill try to say good things about GML in response ;^)Bryan (on Saturday 05 May, 2007) XML is hindering everything, for two reasons (ok, for lots of reasons, but let’s start with two) …

- xml schema is a disaster as you say, and

- people are using xml schema even though they should not.

In the figure above there is a clear distinction between object modelling, and class definition. Object modelling should be done in UML, right now, we’re implementing with GML … but as you rightly suggest, I know folk who are doing their object modelling in XML …

OK, I wasn’t actually planning on a “Why GML sucks” entry, it was a rhetorical, but now you suggest it, it’s not a bad idea to do one! Now I have to make the time :-) …

Bryan (on Tuesday 08 May, 2007) … duplicate comment deleted as requested :-)

Chris Rusbridge (on Thursday 10 May, 2007)

Bryan, your conversationalist said “In my opinion that’s an unsolvable problem, because the way your database models the world is different than mine.” You agreed except for the unsolvable bit. You said “What [GML] absolutely doesn’t give you automatically is code to manipulate someone else’s data objects. What it does give you is a descriptive language you can both use to describe them, and you absolutely have to spend real programming time exploiting the fact you have a common language (so now it’s solvable and possible!)”.

I’m currently reading Geoffrey Bowker “Memory Practices in the Sciences”. It’s a tough read, but again and agin he makes the point (based around domains like geology, biodiversity particularly) that the way databases model the world is based on embedded domain, social, political and other assumptions that are highly variable and competitive. He gives a lot of examples in species naming, for instance, and also in the specification of time (there are many natural clocks) where databases can specify the same thing in deeply different ways, or different things in the same way (animal and plant species with the same name), or just have insufficient 1:1 concept matching to draw the conclusions that appear to be applicable. I’m not at all sure that the modelling processes you describe would bridge these gaps.

The way I’ve been describing this thought so far is “data are not neutral with respect to hypothesis”. I’m not sure it fits this case, but at the least both are suggesting to me that there are real limits on interoperability which go beyond the implications of your response.

I’m not done with Bowker yet, and I might need a fair while to digest his comments. But interim thoughts I have are: hypothesis (politics etc as well) suggest what you measure (and therefore what you do not measure)… presuming that the actual measurement is objective. Hypothesis also changes how you classify things. Much of Bowker’s argument seems to relate to classifications rather than measurements, so at the moment I’m happy that interoperability on measurements is possible. But most measurements are likely to cover both classification/naming and the measure (eg population of Didcot in 1492 depends on deciding what tha area named Didcot was in 1492, which might differ depending on the base you choose).

Not that this is likely to make sense… it’s just I’m worried about interoperability, and I’m not sure that GML can assure it!

PS I find the idea of a “conversation” in the blogsphere hard to get… one cane only hear snippets of the other voice!

Bryan (on Thursday 10 May, 2007) Hi Chris

A quick response: I think the key thing that makes GML a possible intermediary is the assumption that the data models share heritage in the same UML view of the world. In that UML world you ought to be able to unambiguously resolve the differences in classification etc. We discussed this procedure in the Exeter Communique (linked elsewhere in this blog).

What’s also relevant in this context is that the Observation context ought be encoded using concepts that fit into the Observations and Measurements framework (not that using such a framework directly solves the interoperability of the data objects themselves)

Ron Lake (on Thursday 17 May, 2007)

I would like to pick up on the issue of what GML can or cannot add to the interoperability between databases, since at the end of the day that is one of the key issues being discussed.

First I would note that the whole discussion (Savage et al) wrt GML 1.0 and GML 2.0 is a read herring, since both depend on schema descriptions. The only difference is that GML 2. opted to use XML Schema rather than creating a schema language ourselves (see the example quoted by Savage), and is thus led to a clear separation of schemas and instances. Nonetheless both GML 1. and 2.0 (and 3.0) make more or less the same contribution (good or bad) to the issue of database interoperability.

Let’s begin by noting that GML on its own does NOTHING about the fact that I used street when you used road, or that your road has an integer numLanes property while mine has a positive integer numberOfLanes property. Solving this problem automatically is extremely difficult and I would judge well beyond any near term technology. GML provides a middle ground. It allows you to express the schema you do have. It does that using XML Schema and a core set of GML primitives. It allows me to express my schema using the same constructs. Note that when use the same core constructs (geometry, time, topology, coordinate systems) than the interoperability gap is narrowed - but it is not erased. Your schema with numLanes still comes out as numLanes, and my numberOfLanes still comes out as numberOfLanes - we probably would not want it otherwise, since that reflects our view of things. What this does allow us to do however is to SEE the other guys schema and to define the mapping from one to the other. That IS a doable proposition and IS possible and is being done.

GML also makes possible another viewpoint - and that is we can agree on a common schema for a community - just as everyone who uses GML is agreeing on a common structure for the exchanged XML and a common encoding for certain primitives like Point or Polygon. It is too much in my opinion to expect universal agreement on such a schema - if it is hard for a community to do this - how can we expect the whole web to agree? On the other hand it is a doable thing within a restricted community - like all people certain with ship navigation - or all people concerned with tagging news storied - or all people concerned with commercial aviation. They CAN agree on what a NavAid is and they can agree on how to model it. GML then gives them a way to represent that agreement and to send it to others - and to validate that the data they are exchanging complies with the agreement. Not complete interoperability by any means - but a POSITIVE step forward.

Now I will be the first one to admit that modeling in XML Schema is not everyone’s cup of tea. For this reason GML does not require it - nor even encourage it. Tools exist (e.g. ShapeChange) that can create GML application schemas automatically from UML. Other tools can do the same from relational databases and relational databases that incorporate spatial models like Oracle or ArcSDE or Oracle.