Under the hood of a Digital Twin ESM

In which we peer under the hood of the idea that ephemeral data produced by a digital twin can be used by collaborators who co-designed the digital twin experiment.

- Gratuitous image of a an earth system model from the ECMWF presentation on digital twins.

last time I promulgated a definition of an earth system digital twin being an earth system model which has reached the fourth stage of model maturity, where ephemeral data could be accessed by collaborators who understood (and perhaps) co-designed the experimental design to which the digital twin conforms.

In this post I want to peer under the hood of that statement to understand a bit more about what it could mean. To begin with, let’s introduce some vocabulary:

A “configured model” is run to produce a “simulation” with “output” where both the simulation itself and the output conform to a “numerical experiment” which is defined by some objectives and “numerical requirements” (these terms from Pascoe et al 2020).

(The simulation conforms by virtue of inputs including parameters, initial conditions, forcing data, and even potentially the model code, being configured to conform to numerical requirements. The output data conforms by meeting output data numerical requirements.)

So a digital twin is a system capable of executing a “configured model” in such a way that it produces not only normal “output data” but some special output data, which can be used by the “collaborators”. How and why the model is configured is controlled by the experimental design, but now we need two sorts of output data, with the special output data being defined by new numerical requirements in the definition of the numerical experiment.

That of course is not enough, this digital twin system also has to allow the “collaborators” to execute their own processing on the special output data (hereafter called the “ephemeral data”). How then is to be accomplished?

Before we go there it is useful to address one important generic notion for interacting software systems which exchange data, and one important notion for interacting models or components in a complex environmental model (which is a special case of interacting software systems exchanging data).

The generic notion is that for data to be exchanged between two systems they can either agree on what is being exchanged, or they can agree on a way of describing what is to be exchanged. The former can allow significant complexity and is usually relatively inflexible, we term that “strong binding”; the latter allows a lot of flexibility which must be supported (to some extent) in code, we term that “weak binding”. In general the former doesn’t need agreement on types, the latter does, so to do weak binding requires strong typing (software contracts define exactly what the data being exchanged means and is organised).

When two environmental models or model components (A and B) are exchanging data, and when they influencing each other, we tend to call this “coupling”, and when this is done inside a model it is nearly always done with strong binding. A is forcing B and B is forcing A. However, when A forces B, but B really has no influence on A, we can talk about A driving B, and the nature of the binding can be quite flexible. In particular, A never really needs to care about B, beyond ensuring that the data to be exchanged is understood by B - if there are many possible B’s, then the most efficient way to do this is with weak binding and strong typing on what is to be exchanged.

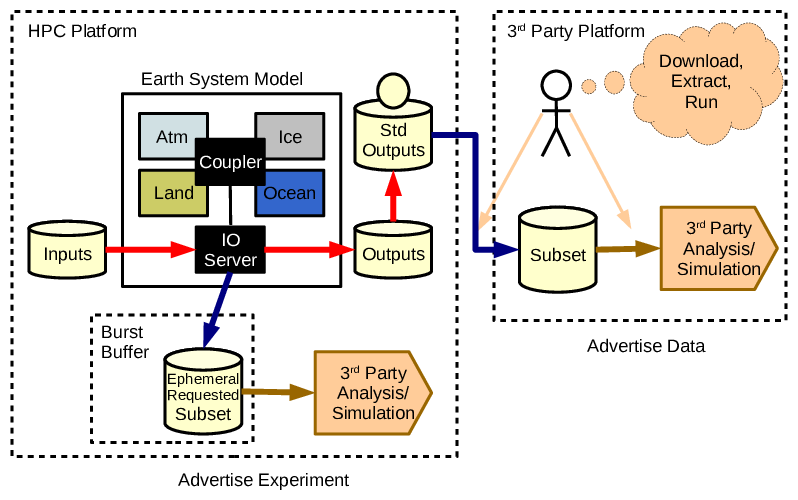

And so to digital twins and collaborators. In the diagram from last time, we can expand a little bit more on the detail:

- Components are coupled inside the model, and collaborators with other models can use the ephemeral data to drive their models

Of course this only works if the infrastructure is set up to allow collaborators to do that, and the experimental design delivers on their requirements, both in terms of producing appropriate ephemeral data and in terms of appropriate scientific configuration.

In practice, “the infrastructure is set up to allow that” means that collaborators can load their code and get it to run “somehow adjacent in the computing system” while the ephemeral data exists. Clearly such collaborators need access to the compute environment, and have access to the appropriate resources. Of necessity this will limit the number of such collaborators compared with those who could consume normal data output via some data repository interface. However, in practice, “collaborators” and “data consumers” really only differ in whether or not they have system access, and how they engage with the experimental design and output data requirements.

There are a couple of underlying assumptions to all this:

- Collaborators need to analyse or drive their models with data products which would not make it into standard output data streams because of volume or other constraints.

- The number of collaborators, and the resources they need, can be constrained by the digital twin provider (and their system provider).

Notwithstanding all this, some ephemeral data use-case might best be met by expecting collaborators to run their models on other systems, the model running on the digital twin system may just be a data connector which pours data out across a wide area network.