On scientific software - a beginning

All the opprobrium for Neil Ferguson’s epidemiological code has got to me. Enough that I’m going to commit myself to a series of blog posts, after a long silence here … (note that I have not committed to the interval period though!)

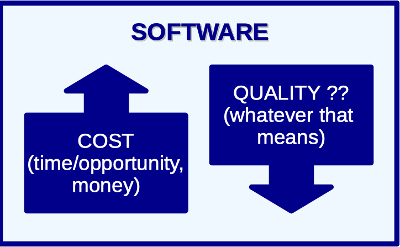

Of course we should all write great quality software, but that takes time and money, not things on common offer for academics. Contrary to popular opinion, most academics I know work long hours, trying to keep teaching, research funding, and actual1 research going. Refactoring software can be fairly low on the priority list, although, actually most of us like doing it … (it’s much more fun than marking)!

There is no absolute measure of software quality - really. there is not! Defect density, conformance to norms, matching requirements (there are more, lot’s more, but that’s enough for now): All useful metrics, but quality, like beauty, is in the eye of the beholder. Does he/she/it do it for you? Do you know when to dance, when to trust, and when to ignore? (You can love someone, but have to ignore some things from time to time.)

Just one defect can bring a plane down. Beautiful software can be garbage, and requirements can be insufficient. On the other hand, if you know the software can do a particular job, and you’ve used it for that before, and you’re not taking it out of it’s comfort zone, you can dance, you can trust, and you know what to ignore.

If you write code in a team, then things change a lot: you need to encode your knowledge of defects, you need to communicate with each other via standardised ways of doing things, and you need to keep registers of issues and compliance tests so people know what can and can’t be done. You don’t dance unless you understand the steps, you don’t trust unless you’ve read the testing notes, and you don’t do things outside the spec. You can’t build on sand, you need to see the rocks.

Or do you? I haven’t met a tradesperson, be they plumber, brick-layer, or software engineer, who hasn’t rubbished the foundations upon which they need to build. While it’s hard to be constructive when you think you are building on sand … we all need to remember that bricks can be made of sand … and sometimes we have to trust the structural engineer who said “that’s good enough FOR THAT PURPOSE”.

Software engineering involves more than just rules, it involves weighing cost against functionality, just like any other type of engineering. We don’t build bridges engineered to carry fully loaded lorries where we want pedestrian bridges.

Much (but not all) scientific coding is often a lonely endeavour. The most likely person to berate you for your lack of coding standards is yourself, six months later, after a term of teaching2 and thinking of a million other things. At that point you wish you’d done it right because you have to mentally retrace all those steps. Documentation: In the real academic world, where no one pays you for documentation, documentation is first for yourself, six months later. If you are lucky enough to have a team, then yes, for them too, but first, for yourself! It needs to be good enough for you, and not better than that (at least at first).

Well, OK, about that trust thing? Scientific code is about results. In the first instance it’s simply about results, but soon after, really soon after, it’s “can I believe these?”, “how do I validate them?” and “are these even useful anyway?”. These are the questions you should ask yourself, before anyone else ever gets near it.

Maybe this abstract notion of quality of the code matters for that? Maybe it doesn’t. But the answers to those questions and how you established them, they matter a lot. Maybe they are the questions which tell us more about quality than coding standards?

We’ll come back to this, and the difference between code, parameters, and experiments/usage, because those things matter too!

Replies welcome on twitter (@bnlawrence), but please don’t jump the gun, try and keep to the story so far.

-

At some point later on this series I’ll explain why I separated software engineering out from actual research (which on the face of it is an indefensible position, and when I get to it, not one I will defend!) ↩

-

What teaching do you do now Bryan? Well, yes, I know I do bugger-all now, but I do ludicrous amounts of admin, so … ↩