On scientific software - definitions

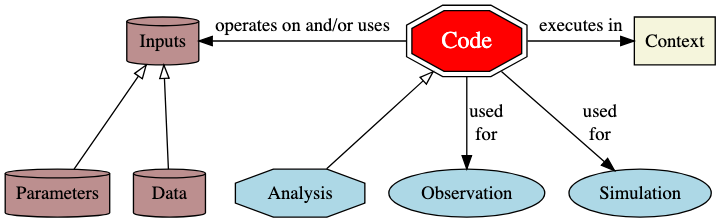

So far in this series on scientific software, I discussed the notion that it might not be that easy to define quality for scientific code (and left some questions hanging about how we might do that), and introduced some scope questions>scope questions about what we mean by science code, and did that by producing a big diagram with lots of stuff.

Today, I want to dig into that diagram a bit further. The headline concept is this:

- Code operates on, and uses input (data and parameters), and executes in some (hardware and software) context. The code may involve collecting and manipulating observations, simulation, and some analysis.

If our interest in the code is about reproducibility, which from last time, many seem to think it is, then we need all of this stuff to reproduce the same results. But is that really “reproducibility” in a scientific sense? Is that really what we want? Being able to re-run some code perfectly would just mean we got the same output again. We’ll come back to that.

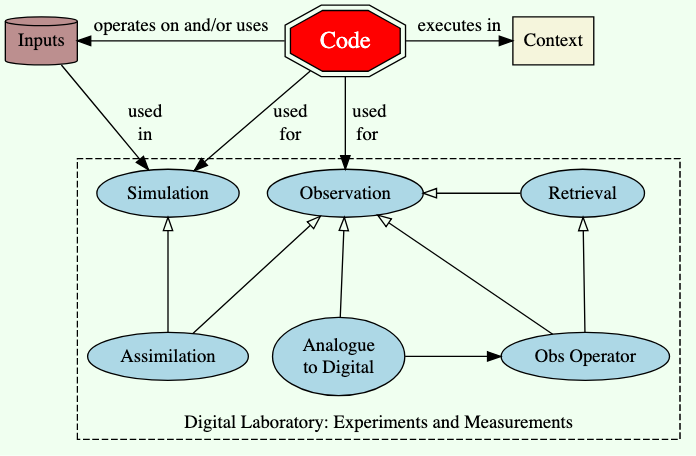

However, I also want to spend some time discussing the piece of the story which is the digital laboratory:

- Much scientific code is associated with making measurements (observations) and/or carrying out simulations. It is important to remember that both simulation and observation use model code.

In any scientific situation which doesn’t involve only analysis of someone else’s data, there will be code which is involved in making/and-or processing data, whether by measurement/observation, or simulation.

We have a clear notion of the involvement of model in carrying out a simulation, but what is less obvious to most, is that there are models involved in nearly all measurements and observations too (in fact, IMHO, the only scientific observation that that doesn’t involve a model is a human describing something or counting something). For example, measurement of anything from space will involve at least code on the space craft to take analogue measurements (e.g voltage) and convert them to digital numbers, followed by some sort of observation operator that turns those raw numbers into some kind of geophysical measurement (e.g. a radar return involves a model of transmission etc). In many cases there will be retrieval code which makes some Bayesian calculation of how observed measurements are related to actual geophysical properties using the error properties of the measurements and some a-priori expectation.

Even measurements in a laboratory have the same basic steps, just a bit less separation in space and time! The idea that observations are somehow pure, and models not, because the former don’t involve assumptions is nonsense.

A particularly important type of observation is one which involves melding simulations and observations together using a process called “Assimilation” - which for some purposes provide the gold standard of making the best use of available information - which is exactly what “Retrieval” does. The difference is usually that assimilation uses the time-varying properties of some a priori and the observations, and retrievals do not (although there are even exceptions there).

What annoys many people, because it’s counter intuitive, is that the error of some “assimilated observation” at one point in space and time can be smaller than an actual measurement at the same point in space and time. This can be shown formally, and arises from the use of information from elsewhere and elsewhen in the assimilation which together lead to quantifiably smaller errors in the product than the measurement itself can have. Of course this relies on measurements elsewhere and elsewhen and a quality model! (As a practical example, the uncertainty error in temperature measurements from radiosondes at some locations can be larger than the uncertainty errors of a quality nowcast of the same data using assimilation in a quality numerical weather prediction model.) However, most of the time “real” measurements are best because of what is called the “representation error”, that is the fact that the simulation model cannot resolve the spatial and temporal scales at which the measurement is made (e.g. see this detailed discussion”). Where assimilation is best is when you need to bring lots of measurements/observations together and provide your best overall estimate of the state of something at one time. In general the use of a model does much better than some random statistical operator (e.g.averaging or kriging).

One more important piece of language for results which involve simulation is to carefully discriminate between the various purposes for which simulation is used. A simple taxonomy could be:

- Forecasting: to predict the actual future of something given knowledge of current state.

- Scenario evaluation: to project one or more possible futures given some assumptions (with or without knowledge of current state)

- A special case of this is to investigate the sensitivity of scenarios to changing the input processes and/or parameters - e.g. What would the world be like without the last century of greenhouse gases? What would happen to this epidemic if we opened primary schools and left secondary schools in lockdown?

- Nowcasting: using all the available information to establish the state of the system now.

- A special case of this is to fully describe some system from partial observations, using the model to interpolate rather than statistics alone.

- Hindcasting: Evaluating how well a forecast system works by using it in prediction mode to predict some particular point in time in the past (and comparing the predictions to the actual outcomes).

That language obviously comes from meteorology and climatology, but it can be applied to any use of simulation.

This long digression is to get my ammunition ready for later on when someone will say “but you can’t trust models”, to which my answer will be “so why do you trust something else?” and “in what circumstances are measurements more or less useful than models which use them”? I also want to avoid statements like “the model was wrong”, when what people really mean is “that scenario didn’t eventuate” (whether or not the model was wrong).

Next time we’ll return to reproducibility, validity, quality all in the context of scientific code, but we’ll be in a position to talk more carefully about what we mean by code, and inputs, and the difference between measurements and observations.