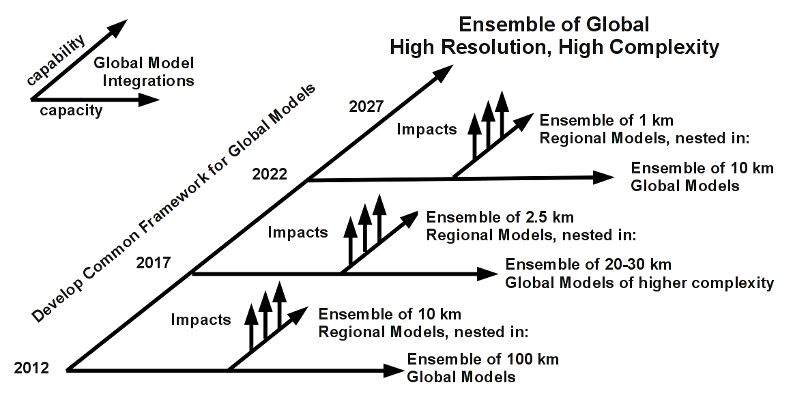

Computing capacity, capability, climate simulations and impacts.

One of the outputs of the IS-ENES project is to be a foresight document outlining where European Earth System modelling should be going in the next decade or two. Of course foresight exercises are fraught with difficulty … but we need to try, especially for ESM, where the lead time on developing a really high end model is probably of the order of 10-20 years, and where supercomputer procurements are multi-year events.

So, there was a meeting near Paris earlier this week that I attended. This blog post is by way of a summary of my take on some of the discussion. It’s absolutely not a summary of the meeting, or a prediction of the eventual outcome of the exercise.

Background

Currently, high end climate simulations require significant HPC, but because many climate models don’t scale well on massively parallel supercomputers, we can’t always use the most “capable” HPC machines. So many of these simulations are considered to be “capacity” computing problems: lots of computing is needed, but they don’t necessarily require (or can’t always use) the highest “capability” machines. However, as we increase resolution and/or complexity in models that do scale, the problem does become a capability problem, they can only be done on the highest performance machines. (That said, often relatively poor scalability goes hand in hand with relatively poor portability, so even if several high end capacity machines are available, the porting effort required tends to encourage running ensembles on one very high end machine: turning capacity problems into capability problems.)

Whenever climate modellers get together we bemoan the simulations we can’t do because of lack of computing - so we’re always in the queue for access to capabilty HPC. However, we want capacity too, because at any given time even if our models were both scalable and portable, we’d be wanting to run ensembles using models at one level of resolution and complexity, and at the same time be developing models of the next generation of complexity and resolution (it takes years to move from one generation of model to the next, as it’s not only a software engineering problem, there are science issues to resolve every time we increase either resolution or complexity). So we’re always on a two track journey: exploiting what is available as capacity, and getting the next generation models ready to run as capacity a few years hence via what is currently a capability job.

To give one real practical example, John Dennis was telling us about NCAR efforts to “go petascale”, and how, just for debugging he actually needed thousands of processors because the bugs couldn’t be reproduced on less … so that’s a capability problem now, but some time in the future (maybe a long time :-), those architectures will look like capacity computing, and we’ll need the climate codes ready to use those computers.

So climate simulation problems of any given complexity/resolution travel on a path from capability to capacity, and ideally that journey involves both sophisticated software engineering and high end climate science.

Moving Forward

In the last decades, much of the community has concentrated on “mitigation” class problems, which are generally of the global scale, and for which global scale models with grid resolutions of hundreds of km are adequate.

Now society and more and more scientists, are turning their minds to the “adaptation” problem as well - we know we’ve got a certain amount of climate change in store (and probably a scary amount), and we need to work out what and where the impacts will be. But the truth is our global scale models aren’t yet suitable on their own for answering these questions, and we think that’s a function of both complexity and resolution. Hence there are a variety of approaches to dealing with the divergence between our ability to predict climate and our our requirements for climate predictions at human scales (typically km or less).

One of those approaches is to use global models to provide “boundary conditions” for “regional models” running at higher resolution. Thus the regional models are effectively running as sophisticated interpolation schemes, providing interpolated results which are consistent with what we know about the dynamics and physics of climate at those resolutions. However, most people agree that it would be far better if we could just avoid regional models and run the climate models at the necessary resolution. However, right now even regional models are too coarse.

Additionally the impacts on the human scale (cities, catchments, mountains etc) need to be further calculated using “Impact Models” which are tailored to the problem of interest.

In the best of all possible worlds, we’d run our global models at a sufficient resolution to resolve the important weather scales (not to predict weather per se, but so we can be confident that the statistics of the weather in our models will behave correctly as the climate changes), and we’d run impact models using statistics generated from those models.

Which brings us back to ensembles. Whatever we do with our climate predictions, we need to ensure that we have enough predictions of the future to gather estimates of the uncertainty in our predictions (and there are at least two sorts of relevant uncertainty: even if we had perfect models, the actual future climate trajectory will be one of many possible future climates, and of course, we don’t have perfect models, and never will).

So, not only do we want more complex higher resolution models, we want ensembles of predictions from those models (and preferably ensembles of predictions by different models, so we can sample both sorts of uncertainty).

How do we get there?

One way forward?

One of the breakout groups at the IS-ENES meeting was considering exactly that issue. Clearly our goal should be able to eventually run predictions at the global scale using whatever resolution is necessary to resolve “weather scales”. We suspect that’s down near the 1km scale (and know it’s certainly below the 50 km scale). But we also know that we only want as much resolution is necessary, and no more - because if we don’t need the extra resolution, we want to use the extra computing power to add complexity to our models (more processes).

So, we came up with the following strategy:

-

On the one strand, we push the sophistication of our global models towards the high resolution higher complexity goal - down the capability path, and at intervals one has the capacity available to run ensembles of the global models so as to provide boundary conditions for regional models.

-

On the other, we run those regional models as ensembles to generate the statistics for the impacts models. Initially with large ensembles of coarser resolution models, but in time, with less diversity in models since it is believed that most of the model part of the uncertainty comes from the boundary conditions as opposed to the characteristics of the regional models themselves. We can then use the extra capacity from using less models to go faster to higher resolution in the regional models.

-

Eventually, the need for regional models should disappear, as either the global models get closer to the resolutions necessary (or they have internal grid refinements) (or both).

-

All the while we improve the software engineering underlying the models so that we can put more energy into maintaining a diversity of scientific models (necessary to get at model uncertainty) and less energy in maintaining a diversity of model frameworks and runtime environments. (See my talk for some aspects of that and other good fun data issues.)

Caveats

-

Like I said above, this is my summary of one part of the discussion, this is no way an outcome of the meeting …

-

With apologies to the rest of the earth system community, just because this is flavoured with atmosphere grid cell resolution, doesn’t mean we were avoiding the rest of the earth system … it’s just a shorthand for increasing resolution where necessary.

-

The timescales on the diagram are complete fiction, the key point I wanted to make was the simultaneous use of both capability and capacity and the need to be pushing towards better models even while producing our best possible predictions.

-

Oh, and by the way, some of those “capacity” machines running some of the members of the global ensembles would be considered “capability” by many. These terms are indicative not categorical.

trackbacks (1)

hpc futures - part one (from “Bryan’s Blog” on (on Tuesday 03 August, 2010)

… By way of organising my thinking about increased resolution, and in some ways, following up on an even older discourse, I’ve spent a bit of time thinking about computing capacity…